Simple cues can trigger powerful memories. It could be the trace smell of baked bread, the muted touch of a wool blanket, seeing the intricate details on a Christmas ornament, tasting a scrumptious dish or hearing the first, chiming notes of a melody. For these four women, a flood of memories started with just three letters: W.A.C.

Women’s Army Corps Veteran insignia

“I heard WAC and felt overwhelmed,” said Philomena Herasingh. “I went instantly back to the late ’60s and ’70s. I was excited and emotional because that was a time I was in a different sort of family. This family unit was filled with adventures, lessons and love. Along the way, (this family was) teaching me compassion and self-determination, traits that I carry to this day.”

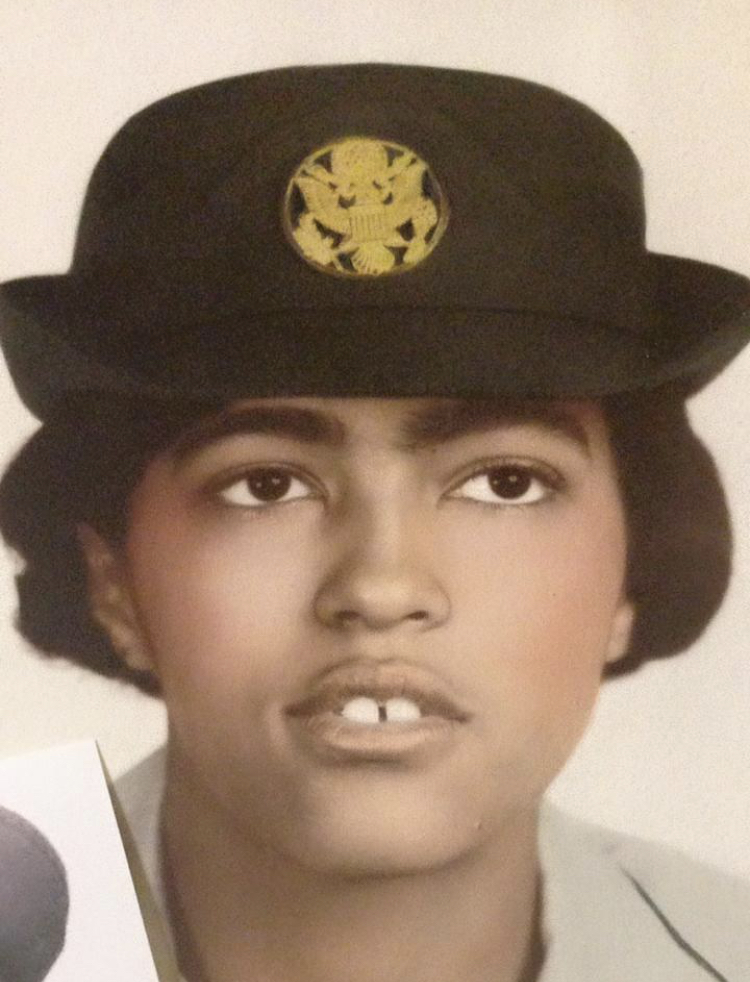

The women, Philomena Herasingh, Patricia “Pattie” Ehline (formerly Muehling and maiden name Carlson), Viola Nathan and Deborah Wallace, are Vietnam Veterans who proudly served as WACs from 1968 to 1971.

The Women’s Army Corps (WAC) was an auxiliary unit of the United States Army created on May 14, 1942. They engaged in World War II, the Korean War and the Vietnam War.

“The WACs taught me to stop being a crybaby,” Wallace said with a hearty laugh. “They taught me it was OK to venture out and stand on my own. I wouldn’t trade that time in my life at all.”

The women didn’t know each other before joining. Wallace and Nathan joined in 1968, while Herasingh joined in 1969. Patti Ehline enlisted in the Army Nurse Corps in 1966 and became a registered nurse the following year.

Nathan attributes her wanderlust and patriotism to the movies. She would save up a quarter to see John Wayne movies at the Roxy Theatre “I loved John Wayne because in his movies, he was so patriotic and caring and he didn’t take any B.S.,” she said. She grew up in the Five Points and Park Hill neighborhoods of Denver, Colorado.

“I love the John Wayne movies too!” laughed Ehline. “And my birth father served in World War II and Korea, so that was there.”

It wouldn’t be until the 1940s that the role of women in the armed forces would take a pivotal turn. In May 1941, the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) was created; that unit later morphed into the WACs. In 1942, a bill added women to the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps, creating the Women Reservists and the Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service (WAVES).

Just five months later, the Coast Guard created its own women’s unit: the SPARs, an acronym that stood for the Coast Guard motto, “Semper Paratus, Always Ready.” Just one year later, two all-female pilot organizations merged to create the Women Air Force Service Pilots (WASPs). Even though each women’s agency had its own identity, their basic functions were similar and best understood by the World War II recruiting slogan, “Free a Man to Fight.” Soon, many women were doing jobs other than nursing. Women began serving in a wide array of military professions, including photography, intelligence analytics, heavy equipment operators and mechanics.

Those interested in medic training were trained at Fort Sam Houston in Texas, while the others were trained in Alabama at Fort McClellan. Nathan, Wallace and Herasingh were sent to Fitzsimons General Hospital in Denver.

After first opening its doors in October 1918, the hospital underwent five name changes. It changed from the U.S. Army General Hospital No. 21 to Fitzsimons General Hospital (in honor of the first American officer killed by enemy action in World War I, 1st Lt. William Thomas Fitzsimons), to Fitzsimons Army Hospital and, finally, in the 1960s to Fitzsimons General Hospital. By 1973, the hospital took its fourth name, Fitzsimons Army Medical Center, which then became U.S. Army Garrison Fitzsimons with the closure of the larger Army base in June 1996.

When the young ladies told their parents about joining, they sold it with the two biggest draws: “The military pays for school and housing,” and, “Don’t worry, I won’t be sent to Vietnam.” Nathan said she was “so excited to get the chance to see the world. But instead, they sent me twelve miles from my house.”

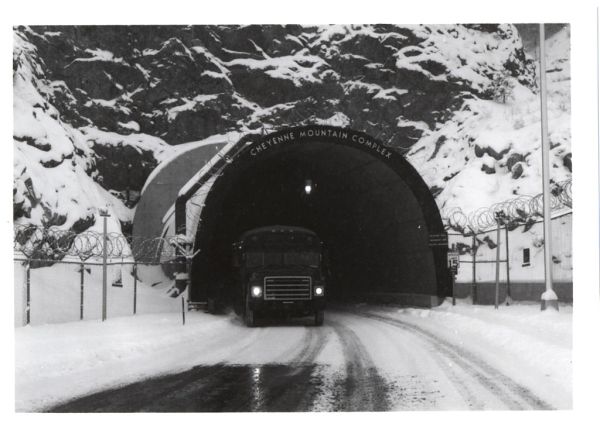

But that wasn’t exactly true for everyone. After basic training at Fort McClellan in Annistion, Alabama, Wallace, Nathan and Herasingh were ultimately stationed in various professions (LPN, podiatry and dentistry, respectively) at Fitzsimons Army Medical Hospital. Not Ehline. As a registered nurse with the U.S. Army Nurse Corps, Ehline was among the thousands of women sent to Vietnam. The young woman from Nebraska was sent to Lai Khê in southern Vietnam. Lai Khê was a former Army base of the Republic of Vietnam and U.S. Army base. She went to Vietnam in 1968, one of the deadliest years of the conflict, during which the United States suffered about 16,899 deaths, according to the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

“Many of the male vets are shocked when they find out that I’m a Vietnam Veteran and I know what it is like to be shelled,” Ehline said. “I was 21 years old when I went over.”

In fact, Lai Khê was arguably one of the most rocketed base camps in the country, having earned the nickname Rocket City. At times, the camp would receive incoming rockets three times per day and twice per night.

“We were being shelled more regularly than the guys in the field. What did they expect? The roof was marked with a big red cross,” she said.

According to the Vietnam Women’s Memorial Foundation, about 90 percent of the estimated 11,000 women who were stationed in Vietnam served as military nurses with the Army, Navy and Air Force. Deployed nurses often worked six days a week on twelve-hour shifts, and were responsible for triage decisions, deciding sometimes who would live and who would not, according to historians. More history can be found at the U.S. Army Women’s Museum in. Fort Lee, Virginia. It is the only museum in the world dedicated to Army women.

The shared history of the other women began from their meeting while stationed at Fitzsimons, affectionately called “Fitz.”

“When I got there, Vi was already there,” Wallace said. “I was alone and so far from home. I told her I needed to go to the store for some things and she said she’d come with me.”

The two would ultimately celebrate more than fifty years of friendship.

Not long afterward they met Philomena. “I guess we all just clicked,” said Wallace.

The women would form more than friendships; they would each find their husbands, all military servicemen, stationed at the medical hospital.

“When you saw one, you saw the other, and the other,” Ret. SSG Trevor Herasingh said. He and Philomena both worked in dentistry; they were married on the base in 1971.

“Vi introduced me to Debbie in 1970 and we’ll have been married fifty years next year in April,” James Wallace said.

“I remember Vi and Phil were always giggling over something; it would make you smile hearing them giggle,” said Ret. SSG Edward Brown Jr.

After being wounded in Vietnam, Brown was a patient at the hospital from 1969 to 1971.

“I had multiple operations there,” he recalled. Brown took most of his injuries on his right side, receiving wounds in his shoulder, chest, hip and leg. The blast perforated his eardrums. He spent three years at Fitzsimons and had around eleven surgeries recovering from that one bad episode. “But when I was better I used to follow her around everywhere. I kept asking until she finally went out with me.”

Viola and Edward Brown were married in 1972.

What impressed the three men about the women was their sense of responsibility, compassion and kindness.

“You couldn’t ask for a better person to cheer you up,” Trevor said of his future wife.

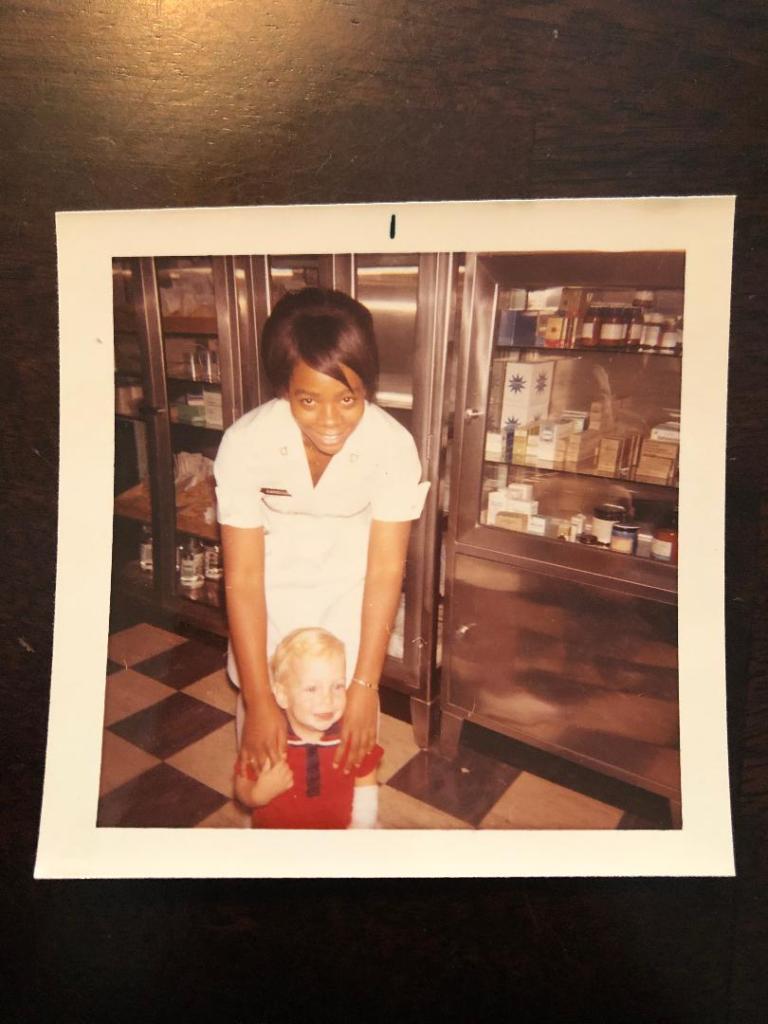

The women would take the time to visit the patients on all wards. “Vi and I would visit with those guys. A lot of times, we would bring them little things they wanted. But most of what they wanted was for someone to spend time. To take the efforts to drop by and say hello and see someone cared and showed compassion,” Philomena said. “Some had no arms or legs and were missing an eye or nose, it was very emotional. But you couldn’t show them how we were feeling, because we were their support system.”

Debbie Wallace recalls trying to follow up with a patient after she left the WACs.

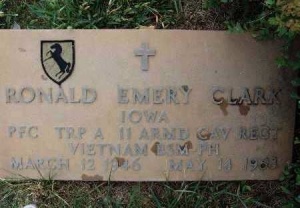

“Ronnie was badly injured and had to have his leg removed due to gangrene. I left the military to start a family, but I worked as a civilian at the NCO (Non-Commissioned Officers) Club. One day I went to check on him. He wasn’t in his bed. They told me he committed suicide,” she said with a distant gaze. “I think of him at times, and let me tell you, once you smell gangrene it stays with you forever.”

Ehline said, “I commend my fellow vets [Herasingh, Nathan, and Wallace]. I patched them up. But they saw and cared for the wounded and disabled after the shock wore off.”

During World War I it was called “shell shock,” and by World War II, it was called “battle fatigue.” For decades afterwards, it didn’t have a name. But just because there isn’t a name, doesn’t mean it isn’t being felt by thousands of military veterans. Five years after the Vietnam War officially ended, a formal name was finalized for the restless nights, sweaty palms, vivid memories and feelings of guilt: Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

There was finally a name for the war being fought off the battlefield and out of the surgical rooms, a struggle that isn’t gender specific. The female veteran is too overlooked in discussions of PTSD. Women vets faced multitudes of stressors coming from both their military service and the sexual harassment and racial and gender discrimination that can come as part of the experience.

Ehline is a survivor of the effects of trauma resulting from PTSD: “I remember hearing the alarms and tearing to the bunker, and it would be dead silent. And we would just wait it out.”

One casualty of note was Sharon Lane, a nurse and U.S. Army first lieutenant who was the only American servicewoman killed as a direct result of enemy fire during the Vietnam War. She was working at Fitzsimons in the tuberculosis ward in 1969 when she got her orders to go to Vietnam.

“I only knew her briefly, she was one of the nurses to be my replacement,” Ehline recalled. “She was killed one week after I left.”

In 1970, Ehline left the military with the rank of first lieutenant. She received the National Defense Service Medal, the Vietnam Service Medal, and the Republic of Vietnam Campaign Medal with 60 Device (an award given by the South Vietnamese government to members of the U.S. military).

The world is finally seeing, acknowledging and honoring women veterans through the hard work of organizations like the Vietnam Women’s Memorial Foundation and Women’s Army Corps Veterans’ Association-Army Women United. The WACVA is the only female veterans’ association chartered by Congress. Alongside various organizations is the Vietnam Women’s Memorial located just north of the Reflecting Pool in Washington, D.C. The memorial was dedicated in 1993.

As a WAC you couldn’t have children. It was a different time. The women got out of the military to start families. Each said they would have liked to stay in the Army. Ehline, Nathan and Wallace live in Colorado, and Herasingh resides in Maryland. Miles may separate the women, but it is their time as WACs that keeps up their sororal bond.

During a Zoom conference call each of the women credited the WACs for building their character by creating the environment to employ compassion and discipline and fostering their growth as women.

“Vi cared about me from the first time I met her. And she has been my strength for all these years,” Wallace said. “She may have started as my friend but now, she’s my sister.”

Nathan began, “I met some wonderful people, like Debbie. She is one of the best things to happen to me. I have no regrets about my time with the WACs. And when necessary, I still take a ‘military shower’ to this day,” she finished with a wide smile.

“My daughter cared for us when my husband and I had COVID,” Herasingh shared with the women. “ I like to think it was her upbringing to be so compassionate. But you know what? I truly learned compassion when I was a WAC. I’m proud to know I passed those lessons to her.”

Ehline said, “I just met Philomena, Viola and Debbie, and I honor these women and all the women that served.”

It has been more than four decades since Congress disbanded the Women’s Army Corps and women were fully integrated into the regular Army, serving in the same units as men. However, the service they learned doesn’t just stop. Now, there are thousands of women, perhaps your mother or grandmother or the older neighbor lady down the street, who now serve as living history to a different era.

Published as guest contributor for History Colorado https://www.historycolorado.org/story/colorado-voices/2020/11/04/women-wac